Untangle the knotted web of investment terms

By Lizelle Steyn

19 October 2019

As someone who gets excited about other people’s journeys to financial freedom, I love to ask what they’re invested in. But few people can speak confidently about their portfolios and investment choices. I often hear ‘I must be invested in Allan Gray funds because I get my statements from them’ from friends that were perhaps not told that you’re under no obligation to invest in a company's funds if you’re using their platform. Another one I frequently hear is ‘I don’t like unit trusts, i'd rather just buy the index,’ from peers who haven't caught on yet that nowadays a unit trust can be an active fund or a passive, index-tracking fund.

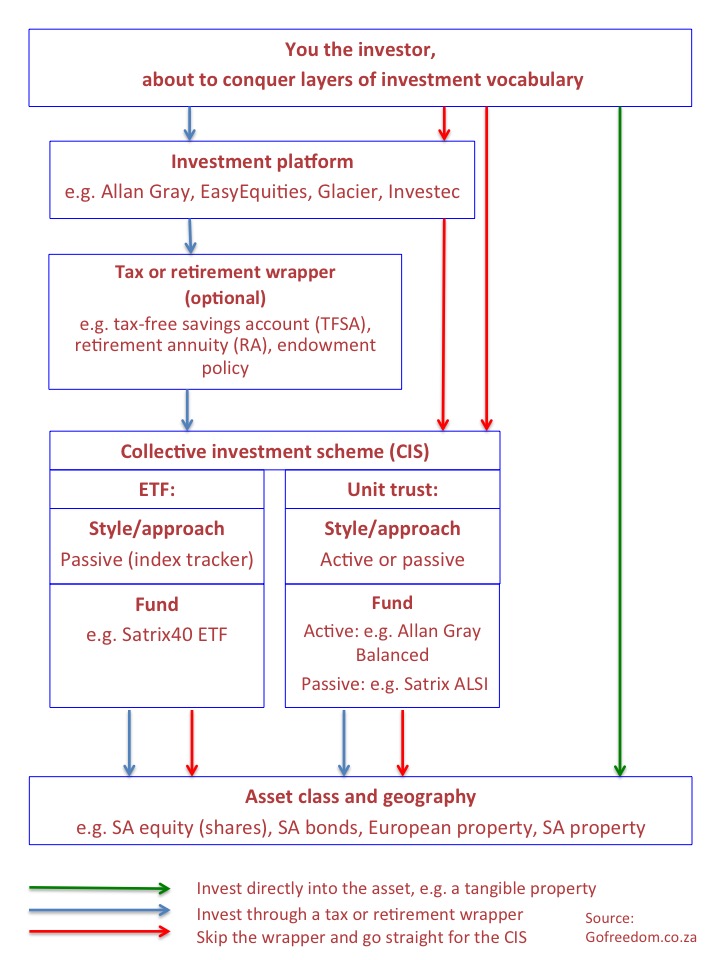

As we dig deeper to find out what exactly they’re invested in, it gets messy trying to untangle this web of terms that our industry uses. Is it possible to capture all the layers and layers investors’ money have to move through to finally end up in a basket of shares? I’m gonna give it a shot, but first we’ll need a picture to help us. I’ll provide the picture. You may want to pour your favourite shot of caffeine.

Bypassing the financial industry is easy – if you have big bucks and don’t pay tax

There is a way to bypass the financial services industry completely, never needing to speak this language. Simply buy an asset, such as a house or apartment or a bar of gold directly. It’s the green route above. You’ll save yourself the headache of having to learn a whole new vocabulary of investment terms. But there are also plenty of cons to following the green route, of which I list only a few:

- you can’t invest small amounts, such as R200 per month. You’ll need thousands.

- You’re not building a diversified portfolio. Even if you buy 10 houses, you’re still 100% exposed to the South African property market and the local economy and interest rates. Great if we’re in a property boom cycle; not so great otherwise.

- You’re potentially missing out on awesome tax breaks.

- You might not be able to sell your asset quickly (liquidity problems).

Using the financial services industry on your financial freedom journey definitely has benefits. The first one is tax.

Using a tax wrapper could – legally - fast forward your financial freedom plan

The first thing you need to look at if you’re ready to boldly step into the world of investments, is a tax-efficient way of investing. There are several 'wrappers' - legal structures that change the nature of your investment so that you'll be subject to different tax and other laws if your investment is wrapped within them. A general rule is that everybody should have an investment wrapped in a tax-free savings account (TFSA) and try and get as close as possible to the 2020/21 tax year R36 000 annual limit – or R3000 per month - that government’s put on this relatively new option. You will pay no tax on a TFSA at any stage of the game (except for a massive penalty from SARS if you invest more than the current R36 000 annual limit). If you’re investing for the long term, make your TFSA contributions your investment priority, assuming you already have a separate emergency fund.

Then, if you have more than R36 000 per year to invest and you’re currently in one of the top 3 SARS income tax brackets, you might want to look at reducing your annual tax bill further by also investing in another common tax wrapper - a retirement annuity (RA). Just remember that with an RA you can’t touch your money until age 55 and will only be able to withdraw one-third of the value on retirement date (the one-third will be partly taxable). An RA is about deferred tax, and makes sense if you plan to be in a lower tax bracket in retirement. Remember to tell SARS about your RA contributions when you e-file, or you could miss out on a tax refund.

And make 100% sure you choose an RA with no hidden commission, complicated bonus systems or penalties. You should be able to add money as and when you want. And stop contributing at any time – penalty free.

For a TFSA you don't need to work through a platform. But if you need a retirement wrapper, or if you want to invest in funds from different investment companies / fund managers, you would need to work through an investment platform.

An investment platform is the face of your investment

Popular investment platforms include Allan Gray, Easy Equities, Glacier, Investec and Stanlib. They are the guys with whom you’ll interact along your investment journey - via call centres, instant messaging, apps, web login and email. So choose wisely. They’ll do a valuation of your investments daily so you can keep track of how they’re growing, and they send you regular statements and your annual tax certificates. Some have more tax wrappers than others, e.g Allan Gray has a preservation fund, an RA, a TFSA and an endowment policy, while Easy Equities currently has only a TFSA and an RA. They all offer collective investment schemes from many different investment companies.

If you don’t need a tax wrapper you can bypass the platform

If you need a tax wrapper, you’ll be following the blue route of my sketch above, starting at the investment platform. If you don’t need it, you can follow any of the red routes. You can either use the platform or go straight to a company offering collective investment schemes with the underlying funds that you’re interested in. For example, if you want to invest in the Coronation Balanced Fund, the Investec Balanced Fund and the Satrix Balanced Fund, you could either use a platform like Allan Gray or Glacier that offer all these funds, and only interact with Allan Gray or Glacier to get your investment values for and transact on all these funds. Or skip a platform and go to Coronation, Investec and Satrix separately to invest in their respective funds and get statements from each company separately. It’s more admin intensive, but will save you the small annual platform fee.

Who even uses the term ‘collective investment scheme’?

Not exactly gliding off the tongue, ‘collective investment scheme’ is the umbrella term for all sorts of funds in which retail investors can pool small – or large – investment amounts together with other investors wanting to invest in the same thing. Collective investment schemes include:

- exchange traded funds (ETFs)

- unit trusts

- real estate investment trusts (REITs)

- retail hedge funds

They’re an almost invisible legal structure that’s needed to invest in funds like the Satrix ALSI40 ETF or the Allan Gray Balanced Fund. So, even if you’re following the blue route, if you’re using a tax wrapper of any of the more modern platforms mentioned here, you will end up in a collective investment scheme. The blue route and the red route merge into a collective investment scheme. ETFs and unit trusts are the most common, which is why I show only these two in the diagram.

ETF or unit trust?

This deserves a post on its own. For now, let’s just say that whether you want an actively or passively managed fund would be the main driver of this decision.

If you choose an active manager, you’ll need a unit trust. If you choose passive, you have the choice between an ETF and a unit trust.

A unit trust can be either passively or actively managed.

An ETF is almost always passive – it tracks an index (also called rules-based investing). It’s generally cheaper than a unit trust, but not always.

Also check whether your current platform actually offers both ETFs and unit trusts. Glacier does for their retirement wrapper, but not for their TFSA. Sygnia offers unit trusts and ETFs. Allan Gray offers only unit trusts currently, and Easy Equities offers only ETFs. Depending on your choice between active and passive, and between ETF and unit trust, you may want to look at signing up with two platforms.

Active or passive?

Passive funds are also called index trackers. To be fair, in reality they’re not that passive, because it takes some work to track an index. An index is what gets reported on in the news every day. Often it’s an entire stock exchange, like the JSE All Share (ALSI) or the S&P 500 or one of the other many stock exchanges across the world. Or only a very specific part of the stock exchange. If you buy the ALSI Top 40, for example, you invest in the top 40 stocks on the JSE.

An active fund is one where a portfolio manager deviates from the index. The fund may, for example, invest in Sasol, but not in Naspers, or have a smaller allocation to Naspers than its weight in the index. A fund manager deviates from the index either because he/she wants to outperform the index, or – and this is often overlooked – wants to protect the investor against large ups and downs. In other words, provide a smoother ride.

In my mind the debate whether active or passive is better is over. They both have a role to play. More on this in a later blog post.

Asset class and geography

And after this labyrinth walk of complex decisions, your money finally ends up in the most important place of all – the underlying assets which either your passive or active fund manager (or both) buy on your behalf. It’s a pity it’s the last layer of the diagram, because I firmly belief – backed by data – that asset allocation is your most important decision. More than a 100 years’ data have shown that, on average equity (shares) outperform cash by more than 4% per year over the long term. For example, choosing shares above cash as an asset class could be the difference between tripling and doubling your investment. We’re talking very long term here, 20 to 30 years of investing, not the freaky past five years where cash actually outperformed shares!

But shares make for a rocky ride, be warned. It’s worth looking at this No risk, no reward infographic that I did for my current employer – with the help of our talented gaphic designer - to get a better idea of the importance of choosing the right asset class with the right amount of risk.

Even though it’s the final station where your money stops and starts to work, your choice from the four asset classes – equity, bonds, property and cash – should be considered before all other decisions. In my case, because I have a moderate and not an aggressive risk profile (i.e. I will take on risk, but don’t stomach dramatic downs in my portfolio well), I blend asset classes, even though equity has proven best over the long term, so I can have a smoother investment experience. And I also include offshore assets, not only SA. Currently 70% of my total portfolio is exposed to the equity asset class (that’s like investing in shares); the remaining 30% is exposed to bonds, cash and property. And geographically, 50% is offshore, 50% in SA.

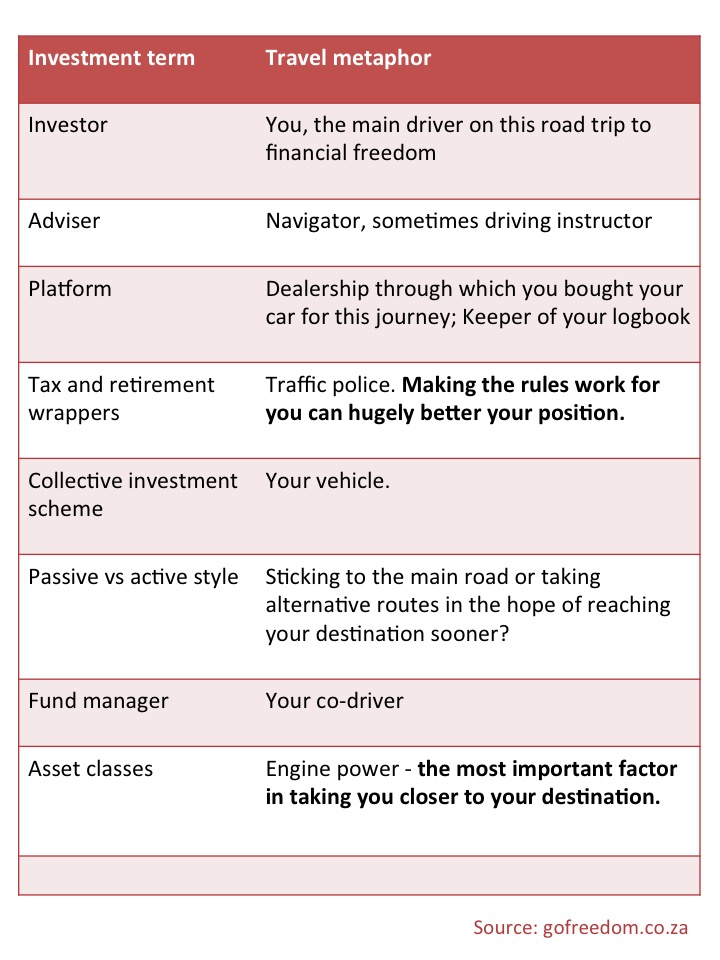

If your investments were a car…

In one last attempt to make the differences between all these investment terms easier to digest, I’ve matched some of the terms that we discussed above with something more fun: travelling.

At the start of your journey to financial freedom, you’d need a dealership (the platform) to buy your car (collective investment scheme) from. You may decide to use an adviser to map out your route and play navigator, or you may do the research yourself. The wrappers are all about sticking to the rules to keep you safe (that’s why you can’t touch your RA money before age 55) and to avoid fines (unnecessary tax). Whether your fund manager uses a passive style, sticking to the main road, or actively tries alternative routes to get you to your destination sooner, he/she is still your co-driver. Continuously adding money to your account, is your share of the driving, making it grow is their share. But a strong engine (enough in the equity and property asset classes) is ultimately what brings you to your destination sooner.

Now it’s over to you. As with learning any new language, don’t be afraid if it comes out all wrong at first. Keep on peppering your adviser or the client services people of your investment platform with questions to find out exactly what you’re invested in and what route your money took to get there. Should the person you're dealing with get impatient, ask to speak to someone else. And keep on practising. Soon you’ll be speaking investments like a pro.