Active vs passive - a game without an end

By Lizelle Steyn

24 March 2021

Credit: Mat Brown

If you’re a DIY investor on the road to financial freedom, you probably already have a few passive (index tracking) funds in your portfolio. And, because of how the investment industry started out, you likely also have some actively managed funds in your older products. The active portion might be a concern to you, because it’s well known that they are more expensive. Are they worth the extra fees? In the active vs passive debate there are a number of arguments that come up regularly. Let’s work through them one by one.

Argument #1: The FIRE movement chooses passive

Mr Money Mustache, the Frugalwoods and almost every FIRE blogger I know choose index tracking funds (passive) for their investment portfolios. This ‘everybody is doing it’ argument is not the one that convinced me to start switching into passive, though. In fact, ‘everybody is doing it’ is a good example of a logical fallacy, also called the bandwagon or ad populum fallacy.

Argument rejected. Mental scorecard: Active = 0; Passive = 0

Argument #2: Warren Buffett recommends index funds

One of the greatest active fund managers of all time, Warren Buffett, famously gave the following advice in 2013:

“My advice to the trustee couldn't be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund.”

Even though he’s made a fortune for his investors with active fund management, he believes most people will be better off by simply choosing an index fund (passive) and some bonds for diversification/ a slight buffer against market volatility.

When a manager as successful as Buffett – and an icon of active investing - starts directing investors towards the competition, I pay attention.

Argument accepted. Active = 0; Passive = 1

Scorecard: Active = 0; Passive = 1

Argument #3: Low fees will give you a higher return

This is the most common argument for choosing passive (index trackers). Even though it feels intuitively correct that lower fees should give you a higher return, it’s only theory until scientifically backed. Lower fees are one of the inputs used in the experiment of testing which of the two give the highest returns. It’s like saying caffeine will give you better exam results without comparing the relevant two sets of results: one set of exam results for students that took caffeine; a separate set of results for students that took the same exam and no caffeine.

Argument rejected.

Let’s go and hunt for comparable results - the historical net returns by active and passive funds respectively. The net returns shown on both index and active funds’ fund fact sheets are a good proxy for the net returns delivered by a fund. If you’re accessing your index fund via an ETF, remember to also deduct the buy-sell spread and all trading costs (brokerage) from the return on the fact sheet. If you access your index or active fund via a unit trust, you might need to deduct a platform fee, if charged. (I’m assuming you’re not using an adviser and no advice fees apply.)

Argument #4: The performance race between active and passive is cyclical

When you start comparing the performance figures of active vs passive, it’s almost guaranteed that studies by active managers conclude in favour of active funds and those used by passive managers rule in favour of passive (index funds). It’s living proof of the saying ‘If you torture the data long enough, it will confess.’

For example, in SA, various ETF providers show how less than half of active managers are able to outperform passive. In contrast, Prudential shows how a large chunk of actively managed assets in SA have outperformed passive.

That drove me to only consider active vs passive studies by unbiased parties. The best read I’ve stumbled on so far is this 2020 publication by Hartford Funds, an investment house offering both actively managed funds and index tracking ETFs to clients.

What Hartford Funds also does correctly in its study is:

- Compare active funds with index tracking funds, NOT with the index. Nobody can invest in an index, only in an index tracking fund, of which the performance is normally slightly worse than the index because of the inevitable fees charged by the fund.

- Compare active with passive unit trust funds, which is the ‘cleanest’ net of fee comparison. If Hartford wanted to compare active unit trust funds with passive ETFs, they would have needed to make an assumption around the average buy-offer spread and brokerage paid on the ETFs and deducted these costs from the ETFs returns to get the true net return of the ETF, as it is impossible to access an ETF without paying these fees. Unit trusts can be bought without paying these access or platform fees.

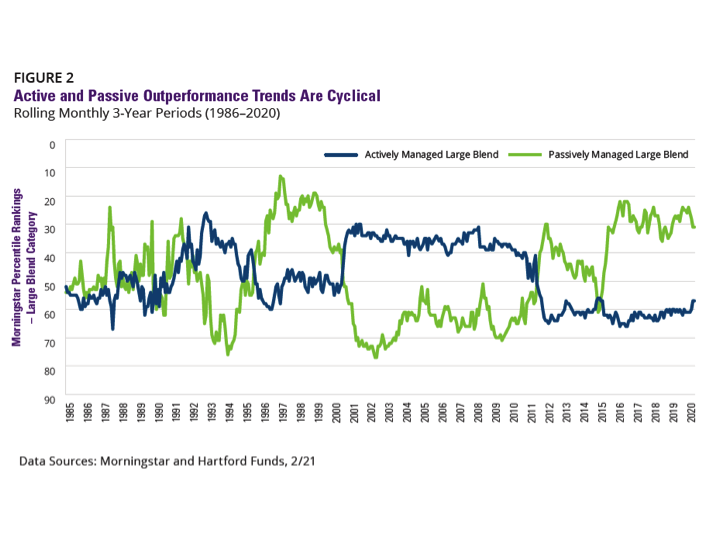

- Look at rolling 3-year returns over the past 35 years. (Figure 2 of Hartford’s report clearly shows the cyclical nature of passive and active.) Using longer-term returns spanning a few decades provides sufficient evidence that each style gets a few years at a time when its rolling 3-year returns are beating the other style.

Each style has its moment in the sun. Active = 1; Passive = 1

Scorecard: Active = 1; Passive = 2

Since switching part of my retirement products to index tracking funds three years back, I’ve seen first hand how sometimes active is ahead and sometimes passive performs best. Over the past three years the actively managed absolute return fund is miles ahead of the index tracker. So, since diversifying into passive, I’ve ‘lost out’. But measured over the past five years, the index tracker is the better performer, and so the cycles will continue in this game that never ends.

Argument #5: Active managers protect the downside better

Because so many active managers are value managers (managers that buy undervalued stocks), their holdings don’t tend to fall as much as the index during a market correction. A stock with a depressed value doesn’t have as far to fall as one with a sky high market price.

The same study by Hartford Funds shows that there were 27 corrections of the S&P 500 index over the past 35 years. Active managers fared better than passive managers during 19 of those 27 corrections, and particularly well during the collapse of the dot-com bubble, simply by being significantly underweight tech stocks.

If the return experience (how volatile your portfolio value is) means nothing to you and you have a stomach like a hardened hyena, and you’re only concerned with the long-term performance, not how you got there, then this argument would mean nothing to you. But to me with my moderately aggressive risk appetite, some downside protection is worth paying a little extra for.

Argument accepted. Active = 1; Passive = 0

Scorecard: Active = 2; Passive = 2

And that’s the current score: 2 each, which is why I hold both active and passive funds in my portfolio. Passive for the low-cost core and active for some downside protection and the potential to outperform the index less the average passive fund’s fees.

Another way to interpret the scorecard is: It doesn't matter whether you choose passive or active. Over long investment periods (20+ years) you are likely to get a very similar result from each.

Active vs passive – what not to do

If you’re going to include both active and index-tracking funds in your portfolio, there are a few common mistakes to avoid:

- Don’t flip between styles: Because the outperformance of active relative to passive is cyclical, don’t make the mistake of switching out of either of the styles after a long bout of underperformance.

- Don’t pay higher fees to a benchmark hugger: There are some active managers with holdings that look remarkably the same as the index. Check the holdings on their fund fact sheets and make sure you’re not paying extra fees for someone who is not willing to take high conviction bets.

- Don’t count on just any active manager to protect downside: Being an active manager doesn’t necessarily make someone better at protecting you against market corrections and crashes. If reducing the ups and downs in your portfolio is important to you, choose a manager with a proven track record in losing less money than the index in down months.

There is no final winner in the active vs passive debate

In the end, there's no final winner in the active vs passive game without an end. The cycles keep on repeating themselves, allowing each style a winning streak. For a very long time now passive has had a good innings. But active will have its victory again. Especially as the pressure mounts on active managers to lower their fees too. Maybe passive deserves a bonus point just for tipping that first lower-fees domino.